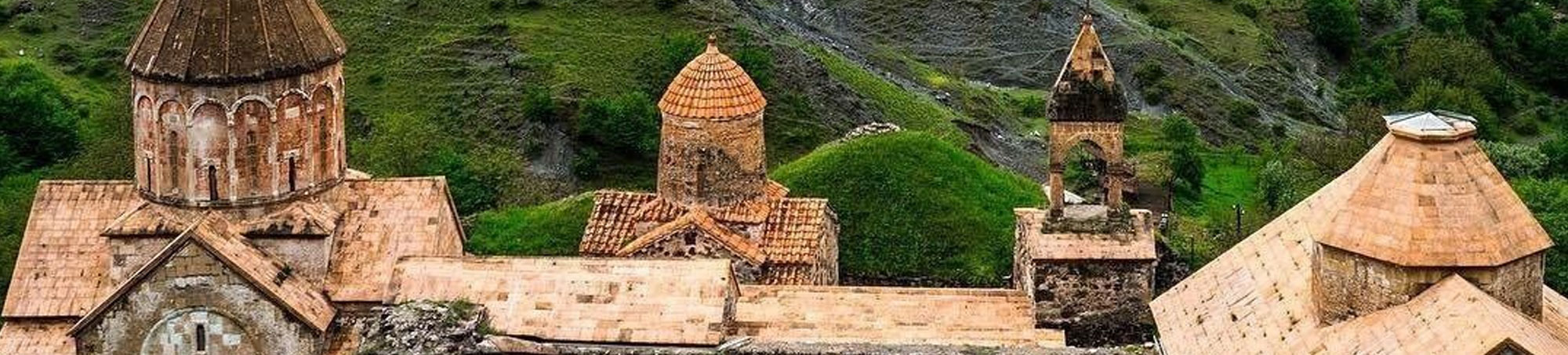

Artsakh’s Gandzasar Monastery (1216 – 1238):

one of the most renowned and

well-preserved ecclesiastical complexes

of medieval Armenia

- Language

- Monuments: Ancient Periods

- Monuments: Middle Ages

- Monuments: Modern Era

- National food

- Culture of Artsakh: gallery

A peculiarity of the region is that few of Artsakh’s monuments date from the post-Arab period of the rise of Armenian kingdoms (ninth to the eleventh centuries), which was a very productive artistic era in other Armenian provinces. The structures that could be attributed to that period are chapels on the cruciform plan with a cupola, such as the church at Varazgom near Kashatagh, the Khunisavank Monastery in Getabaks (now–Gedabey district of Azerbaijan, north to the Republic of Artsakh), and churches with a single nave, such as the church in Parissos. [1]

It was during the post-Seljuk period and the beginning of the Mongol period – during late twelfth and thirteenth centuries – when ecclesiastical architecture blossomed in Artsakh. Monasteries in this era served as active centers of art and scholarship. Most of them contained scriptoria where manuscripts were copied and illuminated. They also were fortified and often served as places of refuge for the population in times of trouble. [2]

Several monastic churches from this period adopted the model used most widely throughout Armenia: a cathedral with a cupola in the inscribed cross plan with two or four angular chambers. Examples include the largest and most complex monasteries of Artsakh: Dadivank (1214–1237), Gandzasar (1216–1238), and Gtichavank (1241–1246). In the case of the Gandzasar and Gtichavank monasteries, the cone over the cupola is umbrella-shaped, a picturesque design that was originally developed by the architects of Armenia’s capital city of Ani, in the tenth century, and subsequently spread to other provinces of the country, including Artsakh.

Like all Armenian monasteries, those in Artsakh reveal great geometric rigor in the layout of buildings. In this regard, the thirteenth century’s Dadivank, the largest monastic complex in Artsakh and all of Eastern Armenia, located in the northwestern corner of the Mardakert District, is a remarkable case. Dadivank was sufficiently well preserved to leave no doubt that it was one of the most complete monasteries in the entire Caucasus. With its Memorial Cathedral of the Holy Virgin in the center, Dadivank has approximately twenty different structures, which are divided into four groups: ecclesiastical, residential, defensive, and ancillary. [3] Dadivank is an active monastery of the Armenian Apostolic Church.

A conspicuous characteristic of Armenian monastic architecture of the thirteenth century is the gavit (also called zhamatoun. The gavits are special square halls usually attached to the western entrance of the church. They were very popular in large monastic complexes where they served as narthexes, assembly rooms and lecture halls, as well as vestibules for receiving pilgrims. Some appear as simple vaulted galleries open to the south (e.g. in the Metz Arrank Monastery); others have an asymmetrical vaulted room with pillars (Gtichavank Monastery); or feature a quadrangular room with four central pillars supporting a pyramidal dome (Dadivank Monastery). In another type of gavit, the vault is supported by a pair of crossed arches – in Horrekavank and Bri Yeghtze monasteries.

The most famous gavit in Nagorno-Karabakh, though, is part of the Gandzasar Monastery. It was built in 1261 and is distinctive for its size and superior quality of workmanship.[1] Its layout corresponds exactly to that of Haghbat (Armenian: Հաղբատ) and Mshakavank (Armenian: Մշակավանք)—two monasteries located in the northern part of Armenia. At the center of the ceiling, the cupola is illuminated by a central window which is adorned with the same stalactite ornaments as in Geghard (Armenian: Գեղարդ) and Harichavank (Armenian: Հառիճավանք) —monasteries in Armenia dating from the early thirteenth century.

The Gandzasar Monastery was the spiritual center of Khachen (Armenian: Խաչեն), the largest and most powerful principality in medieval Artsakh, by virtue of being home to the Katholicosate of Aghvank. Also known as the Holy See of Gandzasar, Katholicosate of Aghvank was one of the territorial subdivisions of the Armenian Apostolic Church. [4]

Gandzasar’s Cathedral of St. Hovhannes Mkrtich – St. John the Baptist – is one of the most well-known Armenian architectural monuments of all times. No surprise, Gandzasar is the number one tourist attraction in the Republic of Artsakh. In its decor, there are elements which relate it to three other monuments, in Armenia, from the early thirteenth century: the colonnade on the drum resembles that of Harichavank (1201 AD), and the great cross with a sculpture of Crucifixion at the top of the facade is also found at Kecharis (1214 AD) and Hovhannavank (1216 – 1250 AD). Gandzasar an active monastery of the Armenian Apostolic Church. The history of the building of the Gandzasar Monastery can be found in the volume History of Armenia written by Kirakos Gandzaketsi or Kirakos of Gandzak (1201-1271). [5]

Gandzasar and Dadivank are also well known for their bas-reliefs that embellish their domes and walls. After the Cathedral of St. Cross on the Lake Van (also known as the Akhtamar Cathedral, in Turkey), Gandzasar contains the largest amount of sculpted decor compared to other architectural ensembles of medieval Armenia. [6] The most famous of Gandzasar’s sculptures are Adam and Eve, Jesus Christ, the Lion (a symbol of the Vakhtangian princes who built both Gandzasar and Dadivank), and the Churchwardens—each holding on his hands a miniature copy of the cathedral. In Dadivank, the most important bas-relief depicts the patrons of the monastery, whose stone images closely resemble those carved on the walls of the Haghbat, Kecharis and Harichavank monasteries, in mainland Armenia. [7]

Although in this period the focus in Artsakh shifted to more complex structures, churches with a single nave continued to be built in large numbers. One example is the monastery of St. Yeghishe Arakyal, also known as the Jrvshtik Monastery, which in Armenian means Longing-for-Water. The monastery stands in the historical county of Jraberd, and has eight single-naved chapels aligned from north to south. One of these chapels is a site of high importance for the Armenians, as it serves as a burial ground for Artsakh’s fifth-century monarch King Vachagan II the Arranshahik. Also known as Vachagan the Pious for his devotion to the Christian faith and support in building a large number of churches throughout the region, King Vachagan is an epic figure whose deeds are immortalized in many of Artsakh’s legends and fairytales. The most famous of those tells how Vachagan fell in love with the beautiful and clever Anahit, who then helped the young king defeat pagan invaders. The legend about Vachagan and Anahit has been translated into English and is available in print from American and European booksellers. [8]

After an interruption that lasted from the fourteenth to the sixteenth centuries, architecture flourished again, in the seventeenth century. Many parish churches were built, and the monasteries, serving as bastions of spiritual, cultural, and scholarly life, were restored and enlarged. The most notable of those is the Yerits Mankants Monastery (Monastery of Three Youths) that was built around 1691 in the county of Jraberd. The monastery was established by the feudal family of Melik-Israelians, Lords of Jraberd, with an apparent purpose to rival the Holy See of Gandzasar and its hereditary patrons — the Hasan-Jalalians, Lords of Khachen. [9] The monastery is dedicated to the Biblical legend about the three young devotees of God from the Book of Daniel – Shadrach, Meshach, and Abednego – who were speared by God after the King of Babylon threw them into a burning furnace for their refusal to worship a Babylonian idol.

Monuments of civil architecture

Mansions of Armenian meliks – Artsakh’s feudal lords – called apararanks, can be found in settlements that served as administrative centers of corresponding principalities of Artsakh. Most of them represent buildings dating from the 17th-19th Centuries. The most notable of them include:

- Mansion of the Melik-Beglarian dynasty in Giulistan, in Shahumian District

- Mansion of the Melik-Avanian dynasty in Togh, in Hadrut District

- Mansion of the Melik-Mnatzakanian dynasty in Getashen

- Mansion of the Melik-Haikazian dynasty in Kashatagh, near Berdzor (Lachin)

- Mansion of the Melik-Dolukhanian family in Tukhnakal, near the city of Stepanakert

To this category of grand feudal mansions belongs the Mansion of the Khan of Karabakh in the city of Shushi.

Princely palaces from earlier epochs, while badly damaged by time, are equally if not more impressive. Among those preserved is the Palace of the Dopian Princes, Lords of Tzar, near Aknaberd (in the Mardakert District). [10]

Artsakh’s medieval inns (called idjevanatoun) comprise a separate category of civil structures. The best-preserved example of those is found near the town of Hadrut.

- Jean-Michel Thierry. Eglises et Couvents du Karabagh, Antelais: Lebanon, 1991, p. 87.

- Tom Masters, Richard Plunkett. Georgia, Armenia & Azerbaijan (Lonely Planet Travel Guides). Lonely Planet Publications; 2 edition (July 2004). ISBN 978-1-74059-138-6, Chapter: Nagorno Karabakh.

- Nicholas Holding. Armenia with Nagorno Karabagh. The Bradt Travel Guide. Second edition (October 1, 2006). ISBN 978-1-84162-163-0, Dadivank.

- Gandzasar. Documents of Armenian Art/Documenti di Architettura Armena Series. Volume 17, Polytechnique and the Armenian Academy of Sciences, Milan, OEMME Edizioni; 1987, p. 14.

- Kirakos Gandzaketsis. History of the Armenians. New York: Sources of the Armenian Tradition, 1986.

- Anatoly L. Yakobson, “From the History of Medieval Armenian Architecture: the Monastery of Gandzasar,” in: Studies in the History of Culture of the Peoples in the East. Moscow-Leningrad. 1960.

- Shahen Mkrtchian. Treasures of Artsakh, Yerevan: Tigran Mets Publishing House, 2002, chapter: Gandzasar

- Robert D San Souci (Author), Raul Colon (Illustrator). Weave of Words. An Armenian Tale Retold, Orchard Books, 1998.

- Boris Baratov. Paradise Laid Waste: A Journey to Karabakh, Lingvist Publishers, Moscow, 1998, chapter: Monastery of the Three Youths.

- Artak Ghulyan. Castles/Palaces) of Meliks of Artsakh and Siunik. Yerevan. 2001